A Brief History of Our Midday Meal

My great-great-great-grandmother did not eat lunch.

Oh, don’t get me wrong. I doubt she was a lunch hater (we are a family of good eaters). Lunch just did not exist in the early part of the 19th century in America. Not how we think of it today, anyway.

Now sandwiched between breakfast and dinner, lunch is a relatively recent meal trend. The word itself is an abbreviation of luncheon, and means a light midday meal.

As a suburban New Jersey child of the 1970s and ’80s, I ate breakfast in the morning (cereal on weekdays, bacon and eggs or pancakes on weekends), lunch at noon-ish (cold cuts or PB&J on white bread) and dinner around 5 or 6 (a meat, a starch, a vegetable).

These lines blurred on the weekend. If we visited family, a marathon mid-afternoon lunch slowly gave way to dinner. The spread included creamy casseroles slowly congealing in their pans on the counter. Mysterious Jell-O salads flipped out of copper molds, shimmering in the light. Bowls of gherkins cozied up to olive loaf sandwiches. No matter which relative’s house, cigarette smoke filled the living room and adult fists held sweaty highball glasses full of brown booze. The youngsters? We got to drink soda instead of milk, and if we sat, it was at the “kids table.”

Was it lunch? Was it dinner? Yes.

Throughout recent history, the main meal of the day has typically been called dinner, whether that meal is eaten around noontime or in the evening. In colonial America, dinner was taken midday. Society was mainly agrarian, and folks rose early for the day’s farm work and chores. By the middle of the day, they were ready to eat a substantial meal. This timing made sense due to the restrictions of using available natural light (candles and fuel were expensive) and the length of time it took to prepare a hearty meal over a fire. A light supper, usually leftovers from dinner, was consumed before bed. These meals were utilitarian, at best, and far from social.

And consider this little etymological tidbit about the origin of the English word dinner. It is from the same roots as the Old French disner (to dine) stemming from the word desjunare, meaning “to break one’s fast.”

Did you catch that?

Breakfast! Dinner means breakfast.

The Wainwrights of Live Oak have been dairy farming for decades. The seventh of nine children, Cheryl Wainwright Finney remembers gathering at a table of 12 for their midday family dinner. They ate food from the garden including new potatoes, green beans, okra, tomatoes and peas of all different kinds. Also, “lots of grits—grits with cheese, grits with gravy, grits with eggs,” said Finney. “Lunch was never ‘lunch,’ and it still isn’t to my dad,” she added.

Finney’s parents, three of her siblings and a number of grandchildren are involved in daily operations at the farm. Wainwright Dairy distributes fresh milk and cheese all over Florida.

Today Cheryl calls the midday meal lunch, switching when she married because calling it dinner confused her husband. These days he brings her lunch to work, perhaps a slice or two of homemade pizza or a sandwich. “Something I can grab hold to,” she said. Busy each day running the creamery, she has little time for even that and generally eats on the fly.

In the mid-1800s when jobs began to move off farms and into towns and cities, a large sit-down meal at home in the middle of the day became impractical. The Industrial Revolution hustled along, moving hand and home production to machine and factory. Among its impacts on lifestyles were people carrying lunch to work and eating it on the job.

From the late 1800s to the 1960s, lunch morphed through phases from eating on the factory floor to enterprising food sellers who set up pushcarts outside places of work—ancestors of today’s food trucks. Cities featured coin-operated automats (food vending machines) that served up sandwiches and beverages for a nickel at the push of a button. As car travel took off, so did fast food, until urban white-collar workers slowed it down again, spending hours decompressing over three-martini lunches.

Luncheon suggests a certain formality or special occasion, as in “the Orchid Society’s Annual Luncheon.” Sources trace the word back to the Middle English nuncheon from none (noon) + schench (drink), and there are chicken vs. egg arguments as to whether the word lunch came before luncheon.

As the meal most commonly eaten away from home, lunch has the potential to be a very public meal. While arguments about word origin are best left to the lexicographers, the way lunch reveals our personal food choices to people beyond our family and those we live with is fascinating.

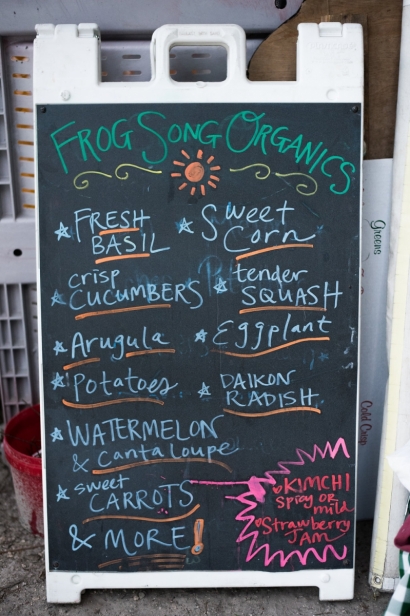

One Northeast Florida farm that still partakes in a more traditional sit-down midday meal is Frog Song Organics in Hawthorne. Located just east of Gainesville, the farm has been supplying vegetables to their own CSA and local markets for five years. Owner Amy Van Scoik said they used to use a cowbell (a family heirloom given to her by her grandmother) to call in workers from the field, but the farm is too big and everybody text messages instead.

The Frog Song field crew gets together buffet style each week, to share food prepared by the farm’s Food and Animal Coordinator Becky Franke. Van Scoik said that “farm lunch” began as a way to entice volunteers to help out before they had any paid staff.

The farm crew eats from the seconds, damaged crops and unsold items from the market. Seasonal veggies are supplemented with beans and rice, and there’s always a cake for birthdays.

“The whole point for us of farming is to have good food to eat,” says Van Scoik.

Samuel Johnson’s cinderblock-sized Dictionary of the English Language (1755) had this definition of lunch: “as much food as one’s hand can hold.” These days, that feels about right. We are a land of convenience, “grab-and-go” options from our grocery stores and eating while driving to our next appointment.

At my job, the bosses buy lunch for the whole staff every Friday. We spread the love between chain restaurants and mom & pop shops, and we fire up the grill once in a while too. I eat at my desk most days, and try not to spill salad on the keyboard.

Whether it’s culled from an edible garden in the schoolyard or ordered from the counter of a food truck parked near your downtown office, gobbled down with co-workers standing in the hot kitchen before you have to jump back into your to-do list, or an occasion to share a bite with family or close friends, lunch is constantly evolving. For many of us, it is a welcome break during the day and the perfect opportunity to refuel. At the very least, it’s a daily pause – before we start thinking about what’s for dinner.