Sound the Alarm, It’s Dinner Time

There is a certain mystique surrounding firefighters. Little kids aspire to be them. Adults read of their exploits or may have firsthand experience meeting them in our time of greatest need. They are heroes among us — the folks who show up for work 24/7, the folks we call when we’re in trouble, the folks who run into the building as we run out.

Do superheroes eat? Of course they eat.

I rolled through the traffic signal at N. Jefferson and W. Duval and stared at the two-story brick building on the intersection’s northeast corner. Bay doors were open to the wet afternoon, and the gleaming grilles and windshields of two fire trucks filled the space. I found a parking place a few doors down in front of the Elks Club and felt instantly at … home. Walking into Jacksonville Fire and Rescue Department (JFRD) Station 4 on a rainy Friday is a walk into my past.

I meandered between the parked fire engines toward the back of JFRD Station 4 and spied a group of men chatting next to the fitness area. Time warped. The firefighters wore the same navy blue t-shirts (with a fire insignia on the chest) tucked into the same navy blue pants. The same courtyard parking area was full of the same pickup trucks. The red brick walls echoed with the same laughter. Involuntary tears sprang to my eyes, nostalgia and homesickness muddled my brain.

My maternal grandfather was a volunteer firefighter, and I grew up at the suburban New Jersey firehouse where my late father was a career dispatcher and volunteer firefighter. As a kid, I’d beg him for change for the soda machine by the break room/kitchen. Sometimes he’d give me a dollar for a slice from Luigi’s Pizza next door. As a young adult, I would drop my dad off for his day shift, then come back in his F-150 after soccer or softball to pick him up.

What most people don’t know is that firehouses and food go hand in hand. JFRD Station 4 Engineer Scott Karpus said, “It is tradition, especially for the larger downtown crews, to cook at the station, then eat together.” There are dozens of firehouse cookbooks. The national fast-casual sandwich chain Firehouse Subs was started on the First Coast by two former firefighting brothers. Cities across the country, including St. Augustine, participate in firehouse chili cook-off contests every year.

In Northeast Florida, if a fire crew doesn’t cook together, it will, at very least, eat together. Nearly every day I see an engine from St. Johns County Fire Rescue Station 9 waiting outside the Vilano Beach Publix as the firefighters shop. St. Augustine Station 40 Firefighter Guerry Bradley cooks for special occasions like holidays and promotion meals. Changing tastes and great discounts from local eateries means a crew may have gotten away from preparing meals as a group, but Bradley said, “Our captain insists we sit down to eat at 6 p.m. every evening.”

Bradley’s crew chief, Captain Jim von Bretzel, noted if a truck goes on a call around mealtime, the rest of the crew waits to eat until they return. For him, eating as a unit is important because it helps build a bond like it did for his family growing up. He said of his crew, “We spend one-third of our life together, and have to depend on each other.” He added that because of constant calls and training, their meal at 6 p.m. is the only time the shift is all together and able to have personal time.

In Jacksonville, there are dozens of fire and rescue stations comprised of three shifts, A, B and C. They work 24 hours on, then 48 hours off in a continuous loop. According to the department’s Public Information Officer Tom Francis, just 1,000 firefighters serve the City of Jacksonville’s nearly one million residents. The “B” shift at JFRD Station 4 is currently made up of 12 men.

What does this have to do with food and eating? During a shift, firefighters aren’t going home for meals. They eat them during their shifts, together at the station. The act of cooking, eating and cleaning up requires teamwork and fosters communication. Food itself is a conversation catalyst. Talking is therapeutic and furthers the bond between the crew.

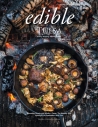

It is Captain Mark Roberts’ turn to cook at Station 4. On the menu are wings, oven-roasted potatoes, corn, tomatoes, okra and rice. When asked who the shift’s best cook is, most of the guys nodded in Roberts’ direction.

To get dinner on the table by 5 p.m. (several firefighters tell me “dinner is at 5 sharp”), the prep starts around 3 in the afternoon. Karpus and Roberts loaded a huge stainless steel bowl full of wings onto trays of the smoker outside in the station’s courtyard. We wandered back into the kitchen. A tray of seasoned chunked potatoes sat on the commercial-sized stove ready for the oven.

A large wooden table dominated the room. The coffee station is in a corner, and the wall behind it sported scribbled upon dry-erase boards. Two white refrigerators stood sentry on the back wall between pantry cabinets. These particular firefighters are coffee-pushers, and a fresh pot is always brewed. Guys walked in and out, their incessant banter and familial ribbing was the kitchen’s soundtrack.

Studies show that families who dine together eat a healthier diet and communicate well, and children who eat at home perform better in school. Work teams that eat together are productive, establish trust and maintain positive working relationships. Taking these ideas further, in 2015, researchers from Cornell University studied firefighters in a large city to see if interacting over food might have an effect on work-group performance.

Turns out, the act of eating together had significant meaning for families and work teams. Even if a routine weeknight meal doesn’t feel special, it is when it’s taken with people to whom you are close. Academics call this commensality.

The Cornell commensality study found that firefighters reported eating together as a central component of keeping their teams operating effectively. These teams were highly cohesive and consistently high performing.A 24-hour shift requires that a couple of meals must be eaten at the firehouse. Station 4’s B shift chips in $10 a day per person for these meals, while an additional $20 a month gets tossed into the “staples” fund for items like coffee, peanut butter, condiments, spices, etc. Food is purchased at local stores, following the week’s sale circular. Engineer Karpus does much of the shopping for B shift at JFRD. He said chicken is a frequent go-to, but special occasions, like celebrating a promotion, might result in steak or crab legs.

As we chatted about training, family and the types of calls they see, the inevitable transpired. A loud two-tone squawk emanated from a speaker on the kitchen’s south wall. I froze. Fast as an alien abduction, the firefighters disappeared. They vaulted out of their chairs, and rushed to their trucks, which pulled out of the station with sirens wailing in under a minute. The alarm was for a fire at a single-family residence. Half-filled coffee cups, a can of Mountain Dew, a cell phone and a pair of reading glasses lay abandoned on the dinner table.

JFRD Public Information Officer Francis noted, “Our annual call volume is 150,000.” That adds up to more than a few interrupted meals for the city’s fire and rescue workers.

When the trucks returned, I asked whether there’d ever been an incident in the station’s kitchen. Say, a fire. There was a uniform pause, then quick sidelong glances and a burst of laughter. One firefighter mumbled, “We’re not at liberty to discuss that,” but another quickly launched into a long story involving bacon on the stove … and flames. What happens at Station 4, stays at Station 4 — and I swore I wouldn’t say anything about the tiny furry kitchen critter, which may, or may not, be named “Bojangles.”

The wings are to be finished on the gas grill, but not before another call, this one for a fall requiring half the crew and one truck. Firefighters remaining at the station keep an eye on the stove and began transferring the wings. Fire is obviously their thing. Station 4 goes through three propane tanks a month, and about three overworked grills are retired each year. Note to the grill makers of the world — B shift considers themselves excellent “product testers.”

JFRD Firefighter Zach Washington, whose dad was also a firefighter at Station 4, set napkins and silverware on the table. I’d wondered earlier if the chuck wagon iron triangle dinner bell hanging with the pots and pans was for show, and on this night, it wasn’t. Washington took it down and clanged it.

Dinner was served buffet-style from the counter near the sink. The guys rustled around as drinks were poured and seats were taken. No one took a bite until all were settled with plates in front of them. Heads bowed as Washington said grace. At “Amen,” forks hit the plates and B shift dug in. It’s 5:42 p.m.

Will dinner look different for firefighters and families in the future? Probably. The foods will change, and the way we eat may too. For now, however, over food — we bond. It’s a time for processing our days and trying to solve the world’s problems, whether we’re superheroes or mere mortals.

Engineer Karpus put it well, “This is family time.” He looked down and gestured at Station 4’s table, “If you need answers to questions, this is where you’ll find them.”