New Life for Old Buildings

“Nothing makes a first impression like a historic building.” This common sentiment of preservationists is the headline of an article on the website for US Foods, a leading foodservice distributor. The article encourages restaurateurs to integrate the character of a historic building with their culinary plan. This is a magical synergy for preservationists and food devotees.

In St. Augustine, there is no shortage of opportunities for collaboration between preservation and epicureanism, as the culinary scene evolves in an environment ripe for reimagining historic buildings. There is a unique diversity of historic buildings, each with their own stories to share, spanning from the Spanish colonial era, the Victorian period, the Gilded Age of Henry Flagler and the postwar period that created eclectic highway buildings along the newly designated “All American Road,” the A1A Scenic and Historic Byway. Throughout my experience in government and preservation nonprofits at the state and local level there is nothing more satisfying than celebrating the reconnection between the fabric of the past with our contemporary culture that includes essential places of social activity.

Restaurants, pubs, coffee shops and the like are community gathering places central to our way of life as they connect family, friends and business partners while celebrating local flavors presented by craftspeople behind the bar and kitchen doors. When combined with the setting of a historic building the human senses are multiplied, feeding our experience and our memories in an incomparable way. We can call this a sense of place and recognize it as a synthesis of artistic and cultural platforms. Walking through the doors of a historic building immediately offers a genuine and inviting space because it is a living piece of the past. It inspires a sense of community, as all its past lives represent pieces of the neighborhood’s narrative and physical fabric. The social and cultural connections of these buildings, some of which are yet to be discovered, are the intuitive reasons for adapting historic buildings into community gathering spaces. However, there are multiple economic benefits that extend beyond the walls.

EATERIES AND HISTORIC PRESERVATION

Often the first hurdle faced by developers, property owners or government agencies is the financial burden of historic building renovations. During my career as a preservationist, while I have had to become a salesperson and recognize the common language of profit margins, I’ve learned there are easy benefits from multiple vantage points. As a heritage tourism destination, St. Augustine’s historic buildings find new life as food and beverage businesses and have positive impacts on the economy. There are many less obvious economic benefits of historic rehabilitation as well. Historic buildings employ skilled laborers and require materials most often sourced locally or regionally, recycling dollars back into the local market.

At the level of local government, restoring a vacant or underutilized building with a vibrant new use produces broad economic benefits by creating a higher producing property tax base. This infusion feeds governmental reinvestment programs like St. Augustine’s community redevelopment areas (CRA) in Downtown and Lincolnville. Government incentives and investment programs help offset investment barriers for historic building renovations that would not otherwise be economically viable redevelopment projects. There is a domino effect when successful investment programs encourage more private investment in neighboring areas.

NEW LIFE IN THE ANCIENT CITY

In the past 10 years, St. Augustine has seen a constant flow of development activity. During that time, some exceptional projects have successfully combined the local preservation review process with historic preservation incentives. The community’s tax base saw a significant jump thanks to the post-rehabilitation tax values of these properties. For instance, repurposed historic buildings including the Ice Plant, St. Augustine Distillery and The Floridian have increased more than 50% in tax value.

HISTORIC LINCOLNVILLE

St. Augustine’s Lincolnville neighborhood is home to Preserved Restaurant. The original structure was the residence of President Thomas Jefferson’s great granddaughter Maria Jefferson Shine in the late 19th century. Over the last 50 years the building witnessed several transitions, including life as a gas station and a grocery store. After the City of St. Augustine intervened and took ownership of the derelict building through a crime prevention program, an inspired chef, a new property owner and a willing contractor collaborated in 2016 to relocate the building on the lot and undertake a major renovation that recreated much of its Victorian appearance and ambience. The property also feeds the St. Augustine Historic CRA improvement program through increased property taxes which are then infused back into the neighborhood.

It can be interesting to observe a repurposed building and wonder about its former life. The Blue Hen on Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr Avenue, for instance, is a small diner in a circa 1917 store, and retains the storefront windows and façade built right up to the sidewalk. But at another juncture in its history the structure also housed a laundromat.

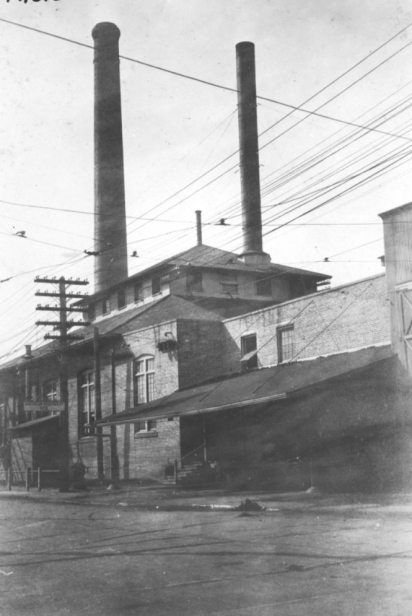

Investing over $3 million in building improvements, the owners of the Ice Plant and St. Augustine Distillery have reincarnated a mostly vacant historic building into a thriving and attractive complex for craft cocktails, farm-to-table creations, education and tourism, all while highlighting the distinct heritage of its past life.

“The distillery was founded and funded by 20 local St. Augustine families that shared a dream of creating an intersection of economic development and social good,” says Philip McDaniel, CEO of the St. Augustine Distillery. “Our intention for restoring the Florida Power & Light Ice Plant was pretty straightforward: to preserve the character (and soul) of the city's oldest and most beloved commercial building into a world class visitor experience and restaurant. We set out to create a singularly unique place where people can learn how spirits are made, from grain to glass; taste the spirits in easy to make cocktails, shop and purchase souvenirs to bring home.”

DOWNTOWN ST. AUGUSTINE

Preserving existing spaces to create a sense of place doesn't make them antiques.The Floridian, a restaurant nestled in the thick of St. Augustine’s Spanish Colonial tourist area, is housed in a rescued Florida vernacular building. While several food businesses had previously operated in this location, it had fallen into decline prior to finding new life as the Floridian. The Flagler-era structure was built circa 1904 as a warehouse-turned-laundry facility during St. Augustine’s Gilded Age hotel heyday. One of the most surprising finds during the renovation was the industrial elevator which was saved and is now on display upstairs.

OTHER NEIGHBORHOODS

Over in the West King Street district of St. Augustine, Bog Brewery makes its home in a 1894 brick building that was once a drug store and jewelry shop. Have an appreciation for mid-century and postwar architecture that came about with the prominence of the personal automobile? Cruise down Anastasia Boulevard and check out the converted 1950s-era roadside auto service buildings, like the 1948 service station being renovated for Hornski’s Record Lounge or the repurposed filling station built in 1955 which now houses Osprey Tacos and Old Coast Ales. And on North San Marco, an old auto supply store built in 1966 is now the home of DOS Coffee and Wine.

Each of these venues features unique food and drink in an environment that offers a canvas for local entertainment and art. These businesses also help our community understand there is value in retaining and repurposing to suit current needs. Proprietors who choose historic preservation are offering the community a gift by investing in its cultural heritage and serving up a homemade sense of place.