Turn on the Heat, Turn up the Flavor

My parents used to drink Maxwell House and Folgers. They alternated what we would smell in the mornings based on which tub of grounds was on sale at Winn Dixie the week they ran out. They wanted effects and familiarity, not flavor. That was thirty years ago.

Since then, coffee, wine, beer, cocktails and chocolate have all experienced their grown-up moment. The changing tastes of the public demanded more than the basics for their meals. Eventually, as palates became more sophisticated, one spicy condiment that can turn the potentially bland into delicious – hot sauce – was due to be elevated.

Hot sauce can get a bad rap, given product labels featuring a man bent over with flames firing or a woman with a burn mark handprint on her behind. It’s an industry that has felt stuck in an early ‘90s beer commercial. This extends beyond just the marketing, as these sauces have often relied on heat to mask a lack of complexity or salt to hide a lack of flavor.

My love of hot sauce started early. I grew up on Louisiana Brand Hot Sauce. My grandfather’s biscuits and gravy recipe demanded it. He grew up in Louisiana during the Depression. They lived in a scrap yard they ran, and I imagine hot sauce was a saving grace for many meals. One Christmas, he gave me a small pocket-sized bottle to carry around. I carried it to school every day of fifth grade and used it on my meals in my South Georgia Catholic school to dress lunches up a bit. One day, I was hit in the nose with the overwhelming smell of rotten eggs and sulfur. I looked everywhere for the source, then confirmed by the red streak down my leg that it was my own pants — my bottle was broken. My leg burned, but I was more broken up about my now limited ability to help my school food taste better.

My obsession with heat and flavor didn’t end in grade school. Years later, I was in culinary school making a barbeque sauce. I kept having my chef instructor try the sauce. I whisked way too much, kept adding and adding in an attempt to build. Finally, Chef told me to slow down. Let the flavors bloom — it takes time for good things to develop, for experimentation to deliver nuance.

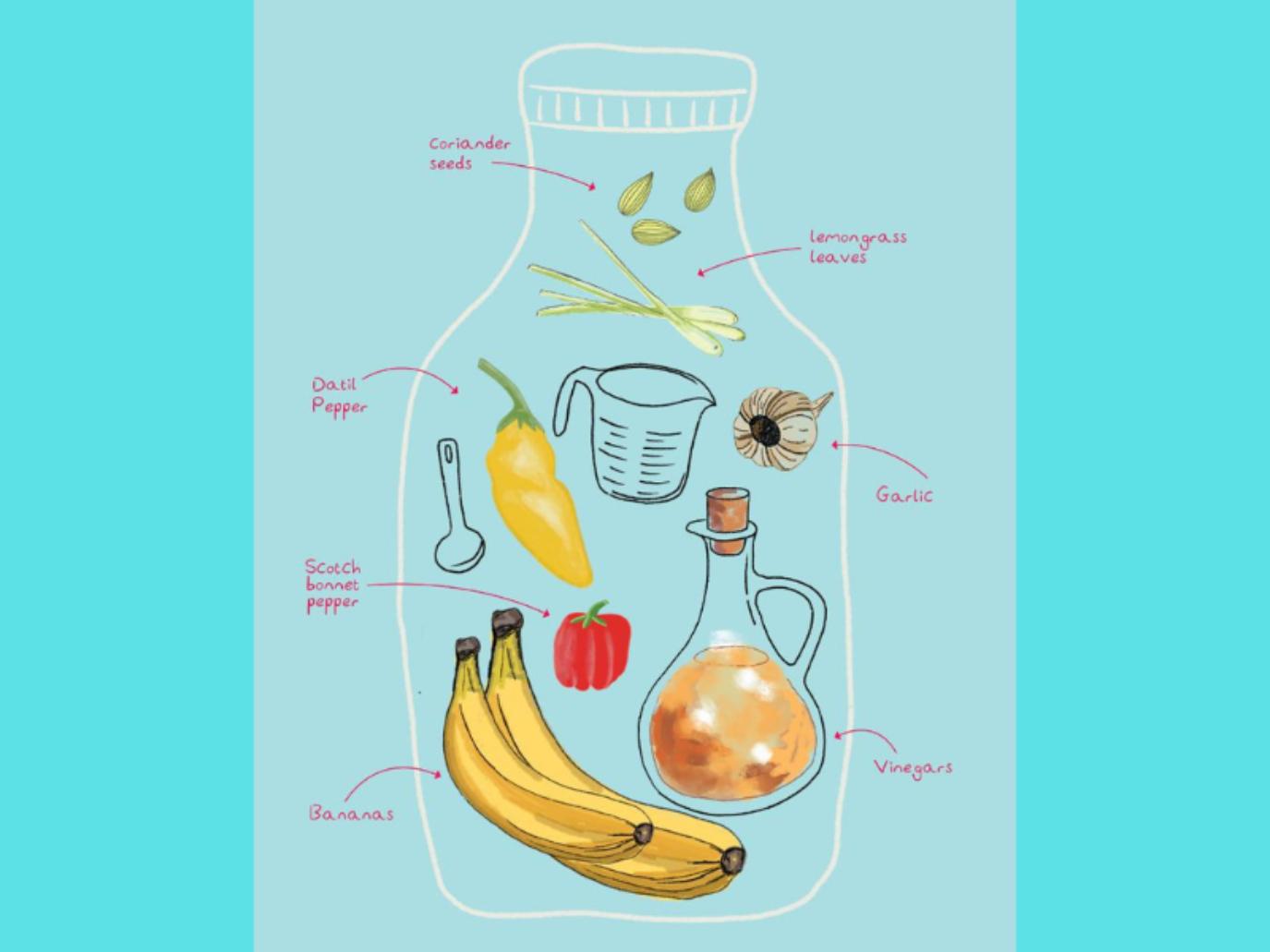

After living in coastal Georgia, a twist of fate brought us back to Florida. Our friends Josh and Claire came to visit, and we acted on an idea that we’d kicked around for a while: to develop our own hot sauce. We wanted to make sauces with all-natural ingredients, to make them accessible to nearly anyone who wanted to try them. We had already done so much research on sauces. Our refrigerator was filled with them. We examined ingredients lists and broke down ratios of their construction. Sauces need certain things: a base, a balance of sweet to salty, texture, heat and some complexity. They should touch on each portion of the palate — tiny micro-bursts of sensation — even if the diner doesn’t realize it.

We went to the local nursery and bought two datil pepper plants. One went back with our friends to coastal Georgia, and we planted one at our home in St. Augustine. The plants grew. And we cooked. I could taste the complexities of the datil pepper. The natural sweetness was unlike any other. Believe me, I began trying (and growing) them all. When we started cooking sauces, we used what we grew. We used all our datil peppers experimenting with sauces, so we bought a Scotch bonnet plant. We named her “Bonnie,” and she produced.

I found that the sauces I admired didn’t start with a ketchup base. Older, established sauces like Pickapeppa use all-natural ingredients to build their sauces from scratch. We took our time, experimented with flavors — fruit, vinegars, curries, rum and spices. When a neighbor brought over a bushel of bananas from their trees, I remembered one of my favorite hot sauces, Key West Gone Bananas. I loved their use of banana as a base. It had a mild sweetness and balanced out naturally salty foods. We realized banana worked to thicken our sauce without using xanthan gum.

Our kitchen began to resemble a mad scientist’s lab. We had scales of different sizes, heat guns, blenders, grinders, hydrometer, test tubes, measuring cups and spoons, straws and pots. All our windows and doors stayed open. We were living as if pepper spray had exploded in our house. From all the chaos and experimentation came a new world of flavor. It felt like something “other,” like we were making potions in our kitchen. Thus Pepper Potion was born, along with Sea Witch Pepper Potions No. 3, No. 4 and No. 5. Sea Witch was different than a traditional hot sauce. We felt that it enhanced the flavors of nearly any food we tried it on.

I often get the question, “What’s the hottest you got?” And I get it. Capsaicin can elicit a euphoric effect. Some sadists love the spanking their tongue can get from Lucifer’s Last Blast, but that’s never been our goal. I often tell those folks that there are other sauces for them. They’re welcome to give ours a go, but I want you to enjoy your drink, not down it in a gulp. I want you to be able to taste the oyster and enjoy the subtlety. Sauce has a job — to improve the taste of a food that arguably should already taste good by itself; to elevate, not overpower. We need to taste our food and enjoy it, because a good meal with the right sauce can be magic.