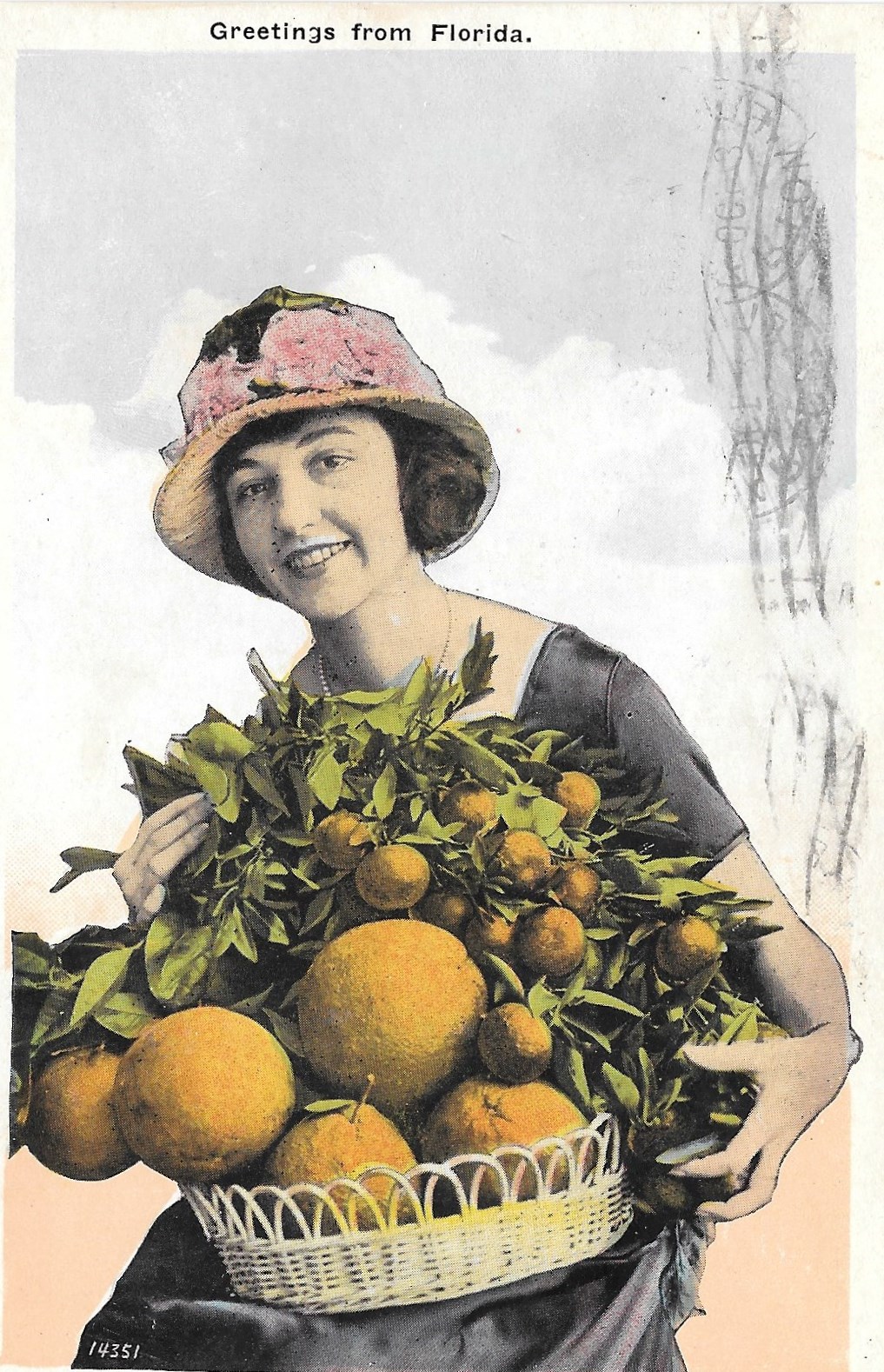

A Brief History of Citrus in Northeast Florida

My fondest memory of Florida’s citrus legacy comes from my teenage years in the 1990s. We would drive through abandoned groves between Ocala and Orlando, windows opened, grabbing oranges as we drove by, filling the backseat. Those overgrown groves, even then, were a testament to the difficulties of growing oranges, left fallow because of the periodic freezes that cut into profits and the onset of citrus greening that destroys trees entirely.

Northeast Florida lacks for commercial citrus these days, especially since the latter half of the 1900s. But there was a time when the scent of oranges filled the air, when the banks of the St. Johns River, especially in Mandarin and Arlington, were thick with groves.

Oranges came to Florida by way of the Spaniards, giving us wild groves by the 1600s, but didn’t become an export until 1764, when we sent a modest 21 barrels to England. It wasn’t until the 1800s that Florida truly caught “orange fever.” By 1811, Zephaniah Kingsley was making a princely sum of $10,000 a year from his Laurel Grove plantation (located in Orange Park), some of which came from his orange grove. In 1814 he’d left Laurel Grove for Kingsley Plantation on Fort George Island, where he planted ample groves, reaping the benefits within 10 years.

The Civil War interrupted citrus production, but by 1867, Harriet Beecher Stowe, who wintered in the Mandarin neighborhood, wrote friends of a property for sale with an orange grove said to yield 75,000 oranges. Freezes in the 1880s destroyed a great many trees, and owners had to battle canker, bugs and other scourges. North Florida grove owners told of the terrible sound of the orange boughs snapping in the bitter cold hard freezes in the 1890s, which devastated the North Florida citrus industry and made South and Central Florida more attractive. Despite those troubles, by the late 1910s Florida had surpassed California in orange production.

By the 1920s, although the industry wasn’t as robust as had been hoped, North Central still had many groves, like the 72-acre farm Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings bought in 1928, located in Hawthorne in Alachua County. You can still see oranges there today, at the Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Historic State Park, where her home and grounds have been preserved. Another local park, Alpine Groves Park in Switzerland, St. Johns County, still features a farmhouse from 1900, and the garage contains much of the machinery for processing fruit. A few orange and lemon trees remain, but most were killed in the freezes of the 1980s.

In St. Augustine, one stalwart fellow decided to carry on despite the deep freezes of the late 1800s. Dr. Reuben B. Garnett marketed his property as a tourist attraction: Dr. Garnett’s Orange Groves. In 1920s and ’30s, his daughter added glass blowing and horseback riding. In the 1940s, the family leased the south end of the land to an entrepreneur, Walter B. Fraser, who owned the Fountain of Youth and the Oldest School House. He dubbed it the Oldest Orange Grove. Bit by bit, the land was sold off or paved over, and in 1962 the majority was bulldozed for a Holiday Inn and Winn-Dixie. These days you’ll find a Doubletree Hotel by Hilton at the old address. The grove and lands bordered what is today Old Mission Avenue, San Sebastian Avenue and San Marco Avenue, all the way to the San Sebastian River.

Today, most of the citrus in Northeast Florida can be found in small groves and private yards, protected by micro-climates. Though it has faded away as an industry in Northeast Florida, our citrus heritage can be found in place names, here and in Central Florida: neighborhoods such as Mandarin (the name was changed from Monroe in 1830 because of the Mandarin orange groves); the city of Citra, founded in 1881 in Central Florida’s Marion County, which still grows oranges today; and Satsuma in Putnam County, named for a cold-hardy variety of Mandarin orange.