Foraging for Wild Edibles in Northeast Florida

Sparks of electricity flash so often across the skies of Florida that the state is known as the lightning capital of the U.S. As such, the state’s ecosystems calibrate accordingly when the requisite fires spark. Oily plant leaves and flaky pine tree bark burn, but the core of the plant or the bulbous root endures. Lightning is the genesis for new vegetation and blooming flowers—thus, the impetus behind Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León’s proclamation of “La Florida” upon landing in 1513 in Northeast Florida. The original inhabitants embraced these cycles of nature, their survival dependent upon the harvested seeds, herbs and flowers.

Thanks to refrigeration and other modern-day conveniences, one no longer has to rely on foraging for food. From a sustainability aspect, appreciating and enjoying the bounty of Northeast Florida’s native plants broadens one’s understanding of the region’s precious, and precarious, biodiversity. From a health perspective, our guts benefit from the microbes and diverse vitamins and nutrients afforded by wild edibles. Fields and forests are filled with plants containing high levels of phytochemicals that ward off disease.

The 54-acre Alpine Groves Park, nestled between the William Bartram Scenic & Historic Highway and the St. Johns River, offers a glimpse into the untold quantities of edibles and medicinal plants — unfortunately often mistaken as weeds — growing all around Northeast Florida. Barely a few yards into the park’s roadside entrance, St. Johns County Department of Parks and Recreation Naturalist AyoLane Halusky steps off a walking trail and kneels down. The raw ingredients for a healthful afternoon snack are within a 270-degree arm’s reach: Muscadine grapes (Vitis rotundifolia); Bullbrier roots that can be boiled for tea; the tendrils of Greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia) that taste like green beans when eaten raw or used in a salad. If the mosquitoes are feisty as you nibble, snip off some nearby deer fennel, which looks like dill, and wipe it on your skin or tuck it behind your ear. Elsewhere, Beautyberries (Callicarpa americana) can be made into jelly, while oak tree acorns are prime for shelling, cooking and grinding into flour. Spanish Needle (Bidens bipinnata) addresses skin issues, and Stinging Nettles (Urtica dioica) can be cooked into greens or used to make tea to alleviate indigestion. These and other edibles can thrive even in a suburban backyard.

As the trail winds deeper into the park, the symphony of the wilderness replaces the noise from nearby traffic. Birds chirp and flutter, insects hum, a light breeze tickles a floor of ferns beneath the trail’s bridge.

“Once you start to learn about edibles, you’ll learn about the birds, the mammals and the insects. You start to see the nature in three dimensions,” Halusky said.

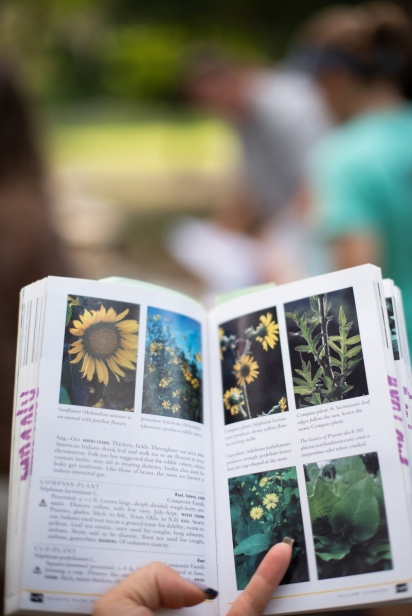

For beginners, plant identification may seem intimidating, especially when the native edibles are surrounded by non-edible — even poisonous — doppelgangers. “You can easily learn to identify poison ivy leaves from the blackberry bush by looking at the leaves. Blackberry has thorns. Poison ivy does not,” Halusky said to a group of guests on a Wild Edibles walk, which is part of the Parks and Recreation Department’s naturalist programming. The key is to familiarize yourself with the plant life within the ecosystem you are interested in exploring. Identify the plant and explore all its uses. Is it native, naturalized or invasive? Press or draw the specimen, which helps you commit it to memory more than simply snapping a picture. Learn its common and scientific names, and cross reference it with other sources.

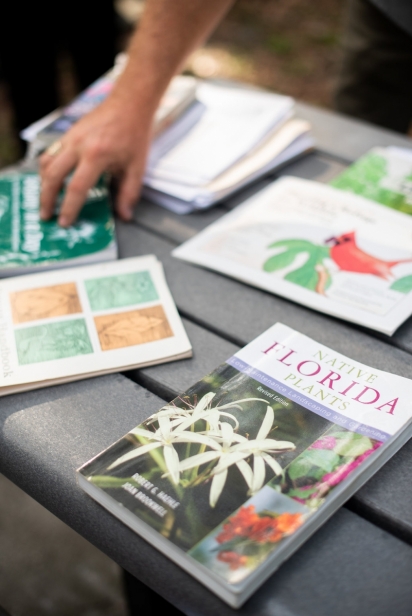

“You should always have at least two to three field guides with you for cross-referencing,” said Halusky. He produced a few of his favorites: Florida’s Wild Flowers and Roadside Plants by C. Ritchie Bell; Eastern Central Medicinal Plants and Herbs by Steven Foster and James Duke; Wildflower Guide by Lawrence Newcomb; Venomous Animals and Poisonous Plants of North America North of Mexico by Steven Foster and Roger Caras; and Wildflowers of Florida Field Guide by Jaret Daniels and Stan Tekiela.

Every day, a new plant within our region becomes endangered or disappears as a result of environmental degradation caused by overdevelopment, the rising salinity of the St. Johns River, invasive species, insecticide applications and/or extreme weather events. Part of the journey in uncovering the treasures of wild edibles and medicinal plants lies in our efforts to reconcile these impacts and live in harmony with nature.

“If you see a native plant, don’t dig it up, but learn how to propagate it,” notes Terra Freeman, an Urban and Commercial Horticulture Extension agent at the UF/IFAS St. Johns County Extension.

Learn about how you can find ways to help a native plant return to a healthy state. Consider spreading seeds or removing invasive plants, suggested Halusky. When foraging, follow the one-fourth rule. Only harvest a small portion of what you need, and leave the rest. Stay at least 200 yards away from any area that has been sprayed with pesticides or could be contaminated in some other way, advised Halusky. Discovering or expanding one's palate for wild edibles is, at its depth, a highly personal experience. Each person’s relationship with nature is unique, perhaps grounded in something we are missing and something we can find. By connecting with the environment and tasting what it offers, we nourish our own body and mind.

“You learn how to be in kinship with nature,” Halusky said.

Want to learn more about foraging and wild edibles in our area? Visit the St. Johns County Naturalist Program at sjcfl.us for more information.